Spoiler Alert: This review contains some minor spoilers about the plot of Oppenheimer.

Content Alert: Oppenheimer contains adult themes, nudity, and graphic language.

If I were to tell you that Hollywood would be releasing a 3-hour film during the summer blockbuster season, primarily about a group of 30-40 year physicists in lab coats trying to solve a problem, you might have your suspicions about the decision. Fortunately for us, the film’s writer and director, Christopher Nolan, is a master storyteller, with both critics and audience members alike praising the film.

When my wife, Colleen, who is much more knowledgeable about these subjects, suggested we see it in IMAX, I was a bit confused. Why would we watch a movie about a group of scientists in IMAX? “Trust me,” she said, (the film’s director) Christopher Nolan filmed it specifically to be seen that way.” Well, as with many things, she was right.

As with his other films, Nolan’s storytelling is accentuated by a superb cast and breathtaking cinematography. One critic called the film “pure visual poetry,” which doesn’t seem much of an overstatement when you immerse yourself in the lines, colors, and shapes that frame Oppenheimer.

From the outset of the film, you are immersed in something special, one that moviegoers have demonstrating by purchasing tickets in droves (Oppenheimer and Barbie combined to make 235.5 million the weekend they opened, the highest box office receipts since pre-covid April of 2019 when Avengers: Endgame was released.

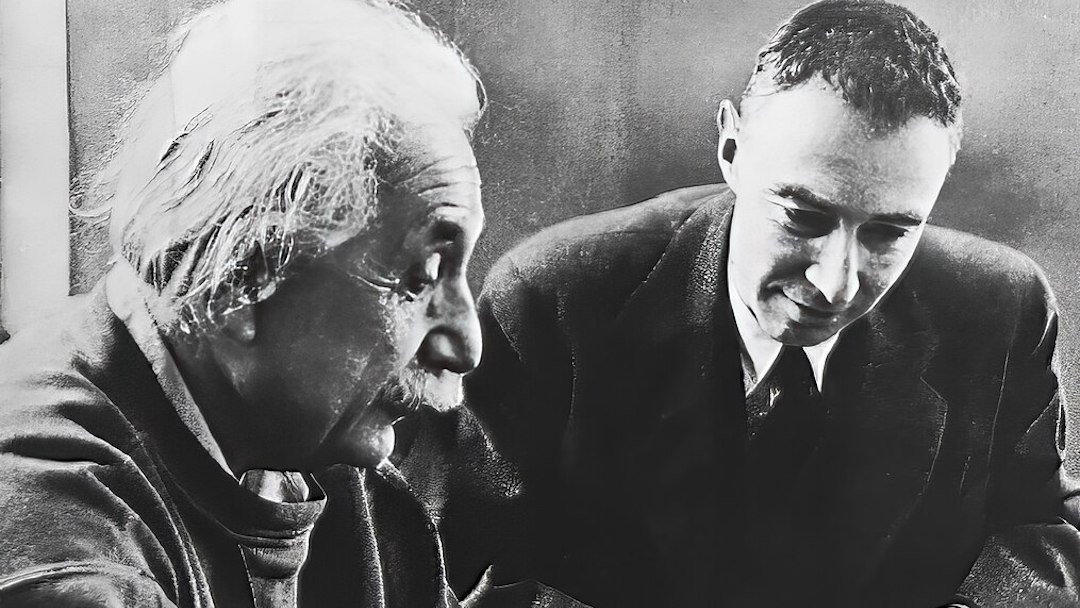

The main character, J. Robert Oppenheimer (played to near perfection by Cillian Murphy), has long been part of modern American consciousness, but his enigmatic character, beginning as a precocious and brilliant scientist (the physics he worked on had already surpassed the work of Einstein), his later fall from grace during the McCarthy era, and subsequent disappearance from public life provide ample fodder for a story to be told.

Nolan tells this story through two general plotlines; the first, filmed in color, called “fission,” presents the rise of Oppenheimer’s brilliant career, beginning with his insatiable quest for knowledge. While he obviously studies physics, we learn in the film that Oppenheimer’s intellectual curiosities are broader. For example, he is reputed to have learned Sanskrit in his free time (as one does). It was from his knowledge of Hindu texts that, when the first nuclear bomb was detonated, the line from the Bhagavad Gita went through his mind: “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.”

The Development of the Bomb

But back to Oppenheimer’s rising career. His quest for knowledge would ultimately bring him to Europe before the start of the Second World War, where he encounters a veritable who’s who of famous physicists. They include, but are not limited to, Werner Heisenberg (Matthias Schweighöfer), Niels Bohr (Kenneth Branagh), Enrico Fermi (Danny Deferrari), and the infamous Klaus Fuchs (Christopher Denham).

The story then pivots to Oppenheimer’s role as leader of the Manhattan Project, which was already underway before he was invited to join the project. At that point in the project, trying to keep thousands of scientists separated but working in the same area without communication across departments was creating a logistical nightmare. “Compartmentalization” (as it was called by the government) was creating a logjam, meaning that the Nazis, or even our “allies,” the Soviets, might complete the bomb first. One of the great tensions of the Manhattan Project lies in just how little each country really knew of the other’s progress. It provides some great tension throughout the film, as it surely must have done in the real lives of those involved.

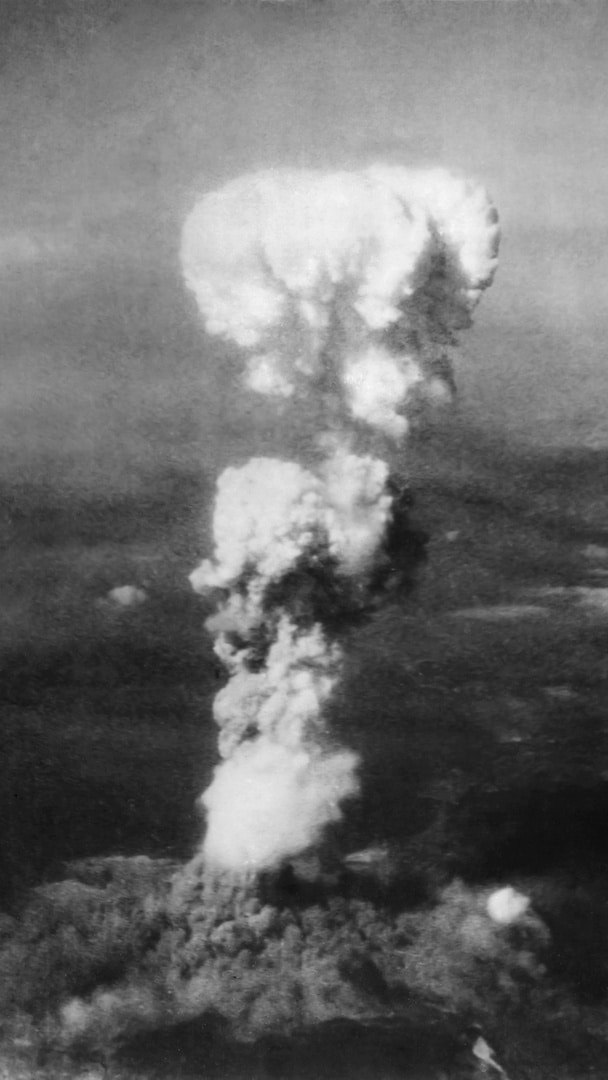

Of course, we know that he succeeds in building the first nuclear bomb, and with it the most destructive weapon in human history. It was a bomb that would ultimately claim the lives of hundreds of thousands men, women, and children from the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. It would therefore, be quite natural for Oppenheimer to be portrayed as a one-dimensional character. He might have been lionized as a modern knight in shining armor who saves the U.S. from a costly invasion of Japan, losing tens, if not hundreds, of thousands of American lives fighting Japan on its home soil. On the other hand, he might have been portrayed as the ultimate villain, blinded by ambition and willing to bring indiscriminate death to the world.

Image courtesy of US Govt. Defense Threat Reduction Agency, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Nolan chose a third option, drawing primarily from the Pulitzer Prize winning book (2005) American Prometheus, by Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin. I haven’t had a chance to read it yet, but, for those interested in Oppenheimer’s biography, consider checking out episodes “Oppenheimer: The Father of the Atom Bomb” and “Oppenheimer: The Witch Hunt” on The Rest is History, a history podcast by British historians Tom Holland and Dominic Sandbrook (TPW recommends).

Oppenheimer, like all of us, is an amalgam of positive and negative qualities. He’s brilliant, hardworking, and drawn to the truth. His relentless effort would help America develop nuclear power faster than Germany, which, if you noticed in the earlier list of physicists, had a substantial edge. When Oppenheimer wanted to learn the very cutting edge of the new physics, he went to Europe. And yet Europe was not able to develop the nuclear bomb—Oppenheimer and his team did. And whatever the other consequences, Oppenheimer’s actions likely cut short the Second World War.

Political Problems

At the same time, Oppenheimer was exceedingly awkward and socially distant, both to those on the outside who didn’t understand his work, and even his own family (and paramours). He’s also idealistic and naive. His dealings with the Communist Party in his early adulthood demonstrated a naivete that most with common sense would realize required more direct action. I’m talking especially about his relationship with the Communist Party in the 1930s and then again during his work on the Manhattan Project.

All of this comes to play in the second major plotline in Oppenheimer, (fusion), which is filmed in black and white (moving back and forth seamlessly, I might add. Again, Nolan is a master cinematographer), featuring two major hearings that would dictate Oppenheimer’s reputation and subsequent fall from grace with the American public. The first was a hearing before the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) in 1954, during the McCarthy era. The hearing was a manufactured “hit job led” by Julian Strauss, a scientist and commissioner of the AECl who would make it his personal mission to destroy Oppenheimer’s career after the two fell out.

Why they did is presented in a somewhat simplified form by Nolan in the film, while the truth is probably a bit more complex and, in all truth, unknown to all but God, Strauss, and Oppenheimer alone. Nevertheless, the film is a cautionary tale, seen over and over again in human history: if you destroy the reputation of another, you often become a target yourself. Without giving too much away, much of the focus of the second half of the film is on a second major hearing, this time before Congress, when Strauss sought a position in President Eisenhower’s cabinet.

Ultimately, Oppenheimer is a great story about a complex character. In one review of the film, Oppenheimer is described primarily as being a film about the main character’s eventual rejection of his greatest work. That to me is simply an oversimplification.

Like the character himself, Oppenheimer was both proud and mournful of the destruction wreaked by his work. While some might attempt to turn his reservations against nuclear proliferation as a sign of an emerging pacifist, this would be an oversimplifcation.

He did struggle with guilt, saying to Truman, “Mr. President, I feel I have blood on my hands.” As an aside: the version of this event in the movie didn’t work for me from a character progression standpoint. We do see the reluctance of J. Robert in the film to escalate the US Nuclear program, but I’m not quite sure we see enough of his misgivings about the deaths inflicted in WWII to experience that scene with the soberness it required. Movies like Oppenheimer are important, not because they offer easy moralisms, but because they force us to ask the question, “what would I do in those same circumstances?”

Putting myself in Oppenheimer’s shoes, would I be willing to fully dedicate myself to creating a bomb that would kill hundreds of thousands, but also save hundreds of thousands more? Do those ends justify these means?

George R. Caron, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Is the great good for the greatest number a warrant for killing so many people, especially in such an indiscriminate manner?

There’s simply no easy answer. How does my faith, specifically in Jesus Christ, who eschewed power and died for us connect to the creation of the world’s first true weapon of mass destruction? These may seem like mere academic questions, but in a democratic society, what we believe will shape public policy.

In truth, we all live in J. Robert Oppenheimer’s world, one that many of us have taken as a given, being born after the Manhattan Project’s completion. And this is no merely theoretical question.

During the previous administration, the US pulled out of the 1987 INF non-proliferation treaty, citing Russian non-compliance. Further, earlier this year, Russia suspended participation in the 2010 New START treaty. Even further, the Russian government is publicly discussing the use of nuclear weapons in either the case of a broader European war or a Ukrainian victory.

The threat of nuclear war has not been so serious since the end of the Cold War. It may seem academic, and that the creation of nuclear weapons was inevitable, whether J. Robert Oppenheimer was involved or not. But looking at his life in particular gives us a unique perspective on history–and how that history comes to bear on us living today. How we choose to think and act in it will certainly have repercussions for generations to come.

Stuart Strachan Jr. is an ordained Presbyterian Pastor as well as the founder and lead curator of the Pastor’s Workshop. His primary passion is equipping the saints for the ministry of the church (Ephesians 4). He loves preaching, teaching, and helping churches cast vision for what it means to follow Jesus in the 21st Century. He has served churches in a variety of capacities in California, Colorado, Pennsylvania, and Washington.

Stu is married to Colleen, who currently serves as a spiritual formation lead at Compassion International in Colorado Springs. Stu and Colleen have two children (Jack and Emma) whom they love deeply.

In his free time, Stu enjoys gardening, golf, reading a good book, and watching baseball.

Don’t Miss

The Latest From Our Blog

New Site Launches Tomorrow!

Watch this Space! Tomorrow (May 29) is the official launch of the new The Pastor's Workshop site! Return to this blog tomorrow morning for a post highlighting the new features and explaining how subscribers can get on and start using the site! Here are some new...

How You Can Prep for Pentecost

This was originally posted on May 12, 2016 on https://huffpost.com Pentecost Came Like Wildfire I'm lying on an ice pack early this morning, doing my back exercises and listening to Pray as You Go, a tool for meditation, with monastery bells, music, and a Bible...

Sacred Spaces: the Church Forests of Ethiopia

Let's Go to Ethiopia! Here’s a fun exercise with a spiritual payoff. Go to Google Maps and view aerial images of the South Gondar zone of Ethiopia. Use this button:When the page loads, you'll see a light brown countryside, mostly farmland. There are thin lines of dark...